- Home

- Jeffrey D. Sachs

To Move the World Page 12

To Move the World Read online

Page 12

“We should also understand,” said Kennedy, “that it has other limits as well.” Signatories could withdraw from the treaty. “Nor does this treaty mean an end to the threat of nuclear war. It will not reduce nuclear stockpiles … it will not restrict their use in time of war.” In fact:

This treaty is not the millennium. It will not resolve all conflicts, or cause the Communists to forego their ambitions, or eliminate the dangers of war. It will not reduce our need for arms or allies or programs of assistance to others.

So what was it if it was not all of these things? “[I]t is an important first step—a step towards peace—a step towards reason—a step away from war.”

Quietly, soberly, Kennedy answered the basic question that would be asked by any citizen: “[W]hat this step can mean to you and to your children and your neighbors.” His answer had four parts:

“First, this treaty can be a step towards reduced world tension and broader areas of agreement.” Other issues—general disarmament, a comprehensive test ban—were ultimate hopes, but not attained in this treaty.

“Second, this treaty can be a step towards freeing the world from the fears and dangers of radioactive fallout.” Kennedy was careful not to oversell this point, though fallout was a cause of great public alarm. “The number of children and grandchildren with cancer in their bones, with leukemia in their blood, or with poison in their lungs might seem statistically small to some,” but “the loss of even one human life … should be of concern to us all.

“Third, this treaty can be a step towards preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to nations not now possessing them.” Kennedy spoke of the possibility that “many other nations” would soon have nuclear capacity, and he reminded his listeners that “if only one thermonuclear bomb were to be dropped on any American, Russian, or any other city … that one bomb could release more destructive power on the inhabitants of that one helpless city than all the bombs dropped in the Second World War”:

Neither the United States nor the Soviet Union nor the United Kingdom nor France can look forward to that day with equanimity. We have a great obligation, all four nuclear powers have a great obligation, to use whatever time remains to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons, to persuade other countries not to test, transfer, acquire, possess, or produce such weapons.

This treaty can be the opening wedge in that campaign.

Kennedy then turned to the last point. “Fourth and finally, this treaty can limit the nuclear arms race in ways which, on balance, will strengthen our Nation’s security far more than the continuation of unrestricted testing.” A nation’s security, Kennedy reminded the country, “does not always increase as its arms increase, when its adversary is doing the same.” Once again, Kennedy explained the fundamental illogic of an arms spiral and the mutual benefits of slowing it, something that he hoped the treaty would help to do. Violations of the treaty—secret testing—would be possible, but the strategic gains would be slight and the costs to the violator’s reputation would be very high. In sum, the treaty, “in our most careful judgment, is safer by far for the United States than an unlimited nuclear arms race.”

Throughout the address, Kennedy did not rely on a single line of jargon, nor did he suggest that the public should simply adopt the views of experts. All was laid out and explained simply and precisely, down to the very choices that the negotiators had made in the previous weeks. And so it was consistent and natural that Kennedy would conclude by calling on all citizens to participate in the upcoming Senate debate:

The Constitution wisely requires the advice and consent of the Senate to all treaties, and that consultation has already begun. All this is as it should be. A document which may mark an historic and constructive opportunity for the world deserves an historic and constructive debate.

It is my hope that all of you will take part in that debate, for this treaty is for all of us. It is particularly for our children and our grandchildren, and they have no lobby here in Washington. This debate will involve military, scientific, and political experts, but it must be not left to them alone. The right and the responsibility are yours.

Kennedy concluded his address with the central theme: that we must pursue a path of peace, one that is uncertain, risky, and challenging, but critical nevertheless. “No one can be certain what the future will bring … But history and our own conscience will judge us harsher if we do not now make every effort to test our hopes by action, and this is the place to begin. According to the ancient Chinese proverb, ‘A journey of a thousand miles must begin with a single step.’ ”

And then came Kennedy’s inimitable call to his countrymen:

My fellow Americans, let us take that first step. Let us, if we can, step back from the shadows of war and seek out the way of peace. And if that journey is a thousand miles, or even more, let history record that we, in this land, at this time, took the first step.

Kennedy’s was a call to action no less direct and stirring than Gandhi’s call to Indians to step toward the sea to collect salt, and thereby free themselves from colonial rule. Kennedy used the word “step” fourteen times in the speech. He knew that peace would require a long journey, beyond a thousand miles and beyond a thousand days, but he cogently laid out the urgency of the first step: ratifying the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

Avoiding Wilson’s Blunders

Kennedy had Senate ratification in mind at every step of the negotiating process. He would not fall into Wilson’s trap, succeeding in negotiating the treaty internationally but then failing to achieve its ratification domestically. Kennedy had an enormous advantage over Wilson, in addition to the obvious one of being able to learn from Wilson’s mistakes. Kennedy, unlike Wilson, was a former senator. There was no way that Kennedy would forget the Senate’s mores, and especially the determined way that senators would defend their prerogative to advise and consent on a major treaty.

From the start, Kennedy considered the domestic politics of the treaty from every vantage point, and pressed his advantage in every manner available. He knew that all parts of the treaty would face scrutiny and that he had to be ready for it. He knew that he would need solid bipartisan support to get two-thirds of the Senate, since some southern Democrats would vote against the treaty. He knew that powerful American thought leaders, if not handled with care, could derail the treaty. In short, he knew that ratification would require a precise campaign whose complexities would rival those of negotiating the treaty itself.

Kennedy had carefully pondered his main points of vulnerability. First, of course, were the European allies. If they bolted, the Senate would surely not go along. Thus, the trip to Europe was vital to bolster his political standing in Europe overall and specifically to solidify West German support for Kennedy’s leadership of the Western alliance, and thus indirectly for the test ban treaty. Second was the military top brass. If the Joint Chiefs of Staff were hostile to the treaty, it would almost certainly fail in the Senate. Third were the natural Senate foes: hardline Republicans and southern Democrats. It was crucial for Kennedy to avoid making the treaty a partisan cause, since the northern and midwestern Democrats simply did not have the votes on their own. Fourth, top nuclear scientists could influence the Senate if they were hostile to a test ban. And fifth, of course, was the general public itself. Broad public support was not sufficient to ensure ratification, but it was surely necessary. Senators would have a much harder time rejecting the treaty in a political environment of broad public support.

Kennedy considered in detail each step of the treaty process from the point of view of ultimate Senate ratification. For example, should Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Macmillan sign the treaty at a summit meeting? Macmillan and Khrushchev wanted that, but Kennedy wisely demurred lest the treaty appear overly identified with Kennedy himself—something that had helped doom Wilson’s League of Nations. He suggested to the other leaders that the foreign ministers sign the treaty, and in the case of the United States, that Secretary of State Rusk

be backed by a bipartisan delegation of senators. After twisting the arms of some reluctant Republican senators who did not want to get too far out in front of the ratification process, Kennedy put together the bipartisan Senate delegation, and the treaty was duly signed in Moscow on August 5. The bipartisan delegation was a signal to the overall Senate, which would now take up consideration of the treaty.

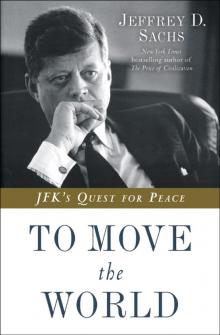

Kennedy with the Joint Chiefs of Staff: Marine Corps general David M. Shoup, Army general Earle G. Wheeler, Air Force general Curtis E. LeMay, President Kennedy, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Maxwell D. Taylor, and chief of naval operations Admiral George W. Anderson Jr. (January 15, 1963).

The next issue was the support, or at least acquiescence, of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “I regard the Chiefs as key to this thing,” Kennedy told Senate majority leader Mike Mansfield. “If we don’t get the Chiefs just right, we can … get blown.” The chiefs have “always been our problem.”5 And they were indeed dragging their feet. Even the moderate chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Maxwell Taylor, was unenthusiastic, but his reservations paled in comparison with those of the head of the air force, General Curtis LeMay.*

LeMay had tangled repeatedly and aggressively with Kennedy, especially during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when LeMay had wanted to bomb the Soviet missile sites. Roswell Gilpatric described that every time Kennedy “had to see LeMay, he ended up in a fit. I mean he just would be frantic at the end of a session with LeMay because, you know, LeMay couldn’t listen or wouldn’t take in, and he would make what Kennedy considered … outrageous proposals that bore no relation to the state of affairs in the 1960s.”6 LeMay had denigrated Kennedy’s blockade strategy in the missile crisis as “appeasement.” Now LeMay might try to derail the test ban treaty, too.

To forestall that danger, Kennedy accepted various reservations to the treaty suggested by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, albeit ones that would not require a renegotiation of terms. This was something that the uncompromising Wilson had refused to do when trying to persuade the Senate to approve his treaty. Kennedy met individually with each service chief and then with the Joint Chiefs as a group, and also had Secretary of State Dean Rusk, CIA director John McCone, and Atomic Energy Commission chairman Glenn Seaborg explain to the Joint Chiefs why each of them supported the treaty.7 At a meeting on July 23, Kennedy agreed to four “safeguards” proposed by the Joint Chiefs:8

1. an “aggressive” underground test program

2. maintenance of “modern” weapons laboratories

3. readiness to resume atmospheric tests promptly

4. improvement of the U.S. capability to monitor Sino-Soviet nuclear activity

The chiefs also consulted with the State Department on the political implications of the treaty. Two days after the treaty was signed, General Taylor wrote to Secretary of State Rusk to ask for his input:

The Joint Chiefs of Staff feel the need of your counsel and that of the Department of State in order to reach a thorough understanding of the implications and consequences of the implementation of this treaty. We recognize that the military considerations falling within our primary field of competence are not the exclusive determinants of the merits of a test ban treaty. In addition, important weight must be given to less tangible factors such as the effect upon world tensions and international relations.9

In the end, the Joint Chiefs were brought on board. Though they were somewhat reluctant converts, they abided by the guidance of the president and the foreign policy leaders on the geopolitical significance of the treaty, and felt satisfied with the safeguard provisions that Kennedy had agreed to.

The Senate Deliberates

All eyes turned toward the Senate on August 8, as President Kennedy submitted the treaty for the Senate’s advice and consent. Two Senate committees held extensive hearings. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by William Fulbright, began on August 12, and called an extensive roster of witnesses, including administration officials, nuclear scientists, and other public leaders. As recounted by Seaborg:

The committee hearings and the subsequent discussion on the Senate floor constituted one of the most intellectually demanding debates in the country’s history. The matters considered included complex military, scientific, political, philosophical, and psychological questions.10

When the Joint Chiefs testified to the Senate regarding the treaty, each averred that he supported the treaty as long as the agreed-upon safeguards were in place. None of them broke ranks, though LeMay did tell Senator Goldwater that had the treaty not already been initialed, he might have opposed it even with the safeguards.11 The chair of the Joint Chiefs, General Taylor, made it explicit that the Joint Chiefs had been part of the negotiating process throughout, and had had ample opportunity to contribute to the process. In their Senate testimony, the Joint Chiefs summarized in this way:

Having weighed all of these factors, it is the judgment of the Joint Chiefs of Staff that, if adequate safeguards are established, the risks inherent in this treaty can be accepted in order to seek the important gains which may be achieved through a stabilization of international relations and a move toward a peaceful environment in which to seek resolution of our differences.12

Administration officials prepared their testimony in great detail. The White House also followed the testimony of high-profile hostile witnesses such as the atomic scientist Edward Teller, known as the “father of the hydrogen bomb,” and encouraged scientists friendly to the treaty to respond to Teller’s objections point by point.13 The head of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Norris Bradbury, was particularly forceful, calling the treaty “the first sign of hope that international nuclear understanding is possible.”14 “If now is not the time to take this chance,” he asked, “what combination of circumstances will ever produce a better time?” President Eisenhower also came out publicly in support of the treaty, writing:

Humankind is urgently seeking for some release from the tensions created by the global struggle between two opposing ideologies … Because each side possesses weapons of incalculable destructive power and with extraordinary efficiency in the means of delivery, world fears and tensions are intensified and, in addition, there is placed upon too much of mankind the costly burdens of an all-out arms race, both nuclear and conventional. As a consequence, any kind of agreement or treaty that plausibly purports to achieve even a modicum of relief from these burdens and tensions is eagerly welcomed by the peoples of the world.15

In the end, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee came down forcefully in favor of the treaty, by a vote of 16 to 1. A second set of hearings, by a subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee, was antagonistic, voting 6 to 1 against the treaty, but with much less political consequence. From the hearings, the treaty moved to the Senate floor on September 9 for debate.

Once again, Kennedy did what Wilson had not: he paid full respect to the Senate leaders of both parties. Sorensen described Kennedy’s personal engagement with senators on the issue:

It paralleled few other efforts which he took place [sic] during the three years of the Kennedy presidency. He personally talked with a great many senators; he worked through the Senate leadership, the Vice President [Lyndon B. Johnson], the legislative liaison officers in the White House under Mr. [Lawrence F.] O’Brien and in the State Department under Mr. [Frederick G.] Dutton. He kept in daily touch with the tactics being used both by the proponents and opponents of the treaty … He met, as I said, with the representatives of the coalition of organizations (which he had helped bring together, I believe) in support of the test ban treaty, counseled them as to how to spend their time and money, which senators they should see, what kind of effort should be made in Washington and back home, and so on. His own speeches and statements at the time were filled with references to this effort.16

Kennedy also sent a detailed letter on September 10 giving certain “unqualified and unequivocal assurance to the members of the Senate, to the entire Congress, and

to the country.”17 In the letter, he reiterated his full backing for the four safeguards advocated by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, as well as for other considerations to address assorted concerns. These considerations included clear statements that the treaty did not affect the U.S. non-recognition of East Germany; that the treaty would not limit the use of nuclear weapons for the defense of the United States; and that the United States would seek necessary international approvals if needed for peaceful uses of nuclear explosions (such as for building canals).

In a masterstroke, he asked the Republican Senate minority leader, Everett Dirksen, to present the letter to the full Senate. In doing so, Dirksen also declared his own endorsement of the treaty, explaining that he would not like it written on his tombstone that “he knew what happened at Hiroshima but he did not take the first step.”†18

The Senate floor debate occurred against the backdrop of a nation strongly mobilized in support of the treaty. Opinion surveys showed that the administration’s round-the-clock efforts at building public support, including Kennedy’s personal meetings with leading newspaper editors and major interest groups, had paid off handsomely. A Harris poll soon after Kennedy’s July 26 speech gave 53 percent “unqualified approval” of the treaty, 29 percent “qualified approval,” and 17 percent opposed.19 By September, the unqualified approval rating had risen to 81 percent. A Gallup poll showed 63 percent approval, 17 percent opposed, and 20 percent without an opinion.

Kennedy signs the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (October 7, 1963).

The Price of Civilization

The Price of Civilization To Move the World

To Move the World