- Home

- Jeffrey D. Sachs

To Move the World Page 3

To Move the World Read online

Page 3

The Kennedy-Khrushchev private letters offer a remarkable interchange regarding the Bay of Pigs. The letters before the Bay of Pigs are highly congenial, the opening moves of confidence building under the tit-for-tat strategy. Khrushchev writes on November 9, 1960, that he hopes Kennedy’s election will mean that “our countries would again follow the line along which they were developing in Franklin Roosevelt’s time,” when the two countries were allies.28 He holds out the prospect of important agreements: “we are ready, for our part, to continue efforts to solve such a pressing problem as disarmament, to settle the German issue through the earliest conclusion of a peace treaty and to reach agreement on other questions.”29 Kennedy responds that “a just and lasting peace will remain a fundamental goal of this nation and a major task of its President.”30 They begin to arrange an early summit meeting.

Yet the tone cracks in Khrushchev’s letter of April 18, two days after the Cuban invasion:

Mr. President, I send you this message in an hour of alarm, fraught with danger for the peace of the whole world. Armed aggression has begun against Cuba. It is a secret to no one that the armed bands invading this country were trained, equipped, and armed in the United States of America.31

“I approach you, Mr. President,” Khrushchev writes, “with an urgent call to put an end to aggression against the Republic of Cuba.”

Kennedy’s answer the same day is dreadfully maladroit. “You are under a serious misapprehension in regard to the events in Cuba,” he replies. “I have previously stated, and I repeat now, that the United States intends no military intervention in Cuba.”32 This patently false denial brings a powerful rebuke from Khrushchev four days later:

I have received your reply of April 18. You write that the United States intends no military intervention in Cuba. But numerous facts known to the whole world—and to the Government of the United States, of course, better than to any one else—speak differently. Despite all assurances to the contrary, it has now been proved beyond doubt that it was precisely the United States which prepared the intervention, financed its arming and transported the gangs of mercenaries that invaded the territory of Cuba.33

Kennedy’s denial marked the second notable U.S. presidential lie to Khrushchev in less than a year. The previous summer, the CIA had pressed Eisenhower to permit another round of U-2 spy flights over the Soviet Union. He reluctantly agreed.* When a U-2 plane was shot down, the CIA and Eisenhower assumed that the pilot, Francis Gary Powers, had been killed and the plane destroyed in the crash. They therefore publicly lied about the mission, claiming that a U.S. weather-research plane had lost its way and crashed in Soviet airspace. Khrushchev then revealed Eisenhower’s lie by producing not only the U-2 wreckage, but the live pilot as well. U.S. perfidy was exposed, and Eisenhower was forced to take responsibility. Yet this was not a simple public relations victory for Khrushchev. It was a bitter setback for Khrushchev’s concept of peaceful coexistence. It also undercut his domestic credibility, as he had initially defended Eisenhower as not responsible for the U-2 flight, and the exposure of Eisenhower’s lie seemed to give credence to the Soviet hardliners who argued that the United States could not be trusted. Khrushchev soon enough would demonstrate his capacity to lie about weighty matters as well; the Cold War was not a game played by saints. Yet the back-to-back prevarications by Eisenhower and Kennedy surely emboldened Khrushchev in his own future dissembling regarding nuclear testing and Cuba.

In a follow-up letter to Kennedy (May 16), Khrushchev acknowledges that “a certain open falling out has taken place in the relations between our countries.”34 Yet he set the ground for an upcoming June meeting with Kennedy in Vienna by emphasizing the key point he sees: the importance of a U.S.-Soviet settlement on Germany. The fate of postwar Germany had proved a constant source of tension between the two superpowers since the dawn of the Cold War, and never more so than when Kennedy took office. It is therefore crucial to revisit some of this history.

At the July 1945 Potsdam conference at the end of World War II, it was agreed that a council of the four major Allied powers (the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union) would administer postwar Germany, but the “how” was left unspecified.35 In the short term, the four powers accepted that Germany would be divided into four occupation zones and that each occupying power would manage its own zone until longer-term arrangements for a unified Germany could be agreed upon. The capital city of Berlin, though falling within the Soviet zone, was also divided among the four powers. But the longer-term arrangements for Germany were never agreed upon, and relations between the West and the Soviet Union quickly deteriorated once there was no common enemy of Hitler to unite them.36 The United States, France, and the United Kingdom soon amalgamated their occupation zones into a single entity, which in 1949 became the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). The Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). The failure to agree on the fate of a unified Germany sowed the seeds for many of the Cold War conflicts that followed.

Herein lay the basic dilemma. The Soviet Union—which had lost more than twenty million soldiers and civilians in World War II—feared a German resurgence, and thereby asserted harsh control over the Soviet occupation zone of Germany. Not only that, but Joseph Stalin, the brutal leader of the Soviet Union since the mid-1920s, ruthlessly created satellite states in Eastern Europe (in Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and elsewhere) under single-party communist rule, thereby establishing a controlling corridor from Russia all the way to the heart of Germany. To the Western powers, these actions seemed to suggest a Soviet plan to dominate all of Europe, if not the world. While U.S. leaders had initially favored deindustrializing Germany at the end of the war to prevent it from again becoming an economic and military power,37 they quickly changed their minds in the face of the perceived Soviet aggression. They instead decided to reindustrialize the western part of Germany as rapidly as possible as a bulwark against the Soviet Union and to strengthen Western Europe generally.38 The Soviet Union viewed the hardening of U.S. positions as a violation of agreements intended to prevent a long-term resurgence of German power.

It’s not hard to see where this led. As West Germany got stronger, Soviet anxieties rose. As the Soviet Union’s anxieties rose, it became more belligerent in response, and the West then became even more determined to rebuild West Germany to resist Soviet domination. This explosive dynamic continued after Kennedy’s assumption of office.

Making things even more difficult for Kennedy was the fact that Eisenhower had proved neither very attentive nor interested in the Soviet concerns vis-à-vis Germany. Eisenhower stood strongly in favor of Germany’s economic and military recovery, in part because he wanted Western Europe to defend itself so that U.S. troops could return home.39 Eisenhower liked neither the cost of stationing U.S. troops in Europe nor the long-term political commitment. Eisenhower believed that U.S. commitments should be tapered down as soon as Europe could take up the burdens of its own defense.40 And if that even meant a Western Europe with nuclear weapons, he was generally for it.

In the final years of the Eisenhower administration, in response to the European desire for nuclear weapons, the United States and NATO—the military alliance of Western powers, formed in 1955—began floating the idea of “nuclear sharing” among the NATO countries, perhaps through a nuclear Multilateral Force (MLF). The United States saw the MLF as a way to share nuclear weapons with allies and give Europe its own deterrent without having to give any one nation full control and the power to launch a nuclear weapon unilaterally.41 This prospect, particularly of West German nuclear access, was a crucial factor in the dramatic heating up of U.S.-Soviet tensions in the lead-up to Kennedy’s presidency. This point is made forcefully by the historian Marc Trachtenberg in A Constructed Peace (1999), one of the most incisive and important historical analyses of this phase of the Cold War.

Kennedy did not yet have a strategy for Germany, and indeed was pressed hard by the

West German leader Konrad Adenauer not to have one. From Adenauer’s point of view, any thaw in relations between the United States and the Soviet Union would likely come at West Germany’s expense. But Kennedy would listen to and learn from Khrushchev’s repeated and heated concerns over Germany, especially concerning Germany’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. Kennedy would eventually break with Adenauer on that question, thereby paving the way to closer cooperation with the Soviet Union. But that breakthrough was still two years in the future, and dire risks were strewn on the path to success.

Berlin Redux

Following the Bay of Pigs debacle, it was now Khrushchev’s turn to misstep badly. With Kennedy on his back foot, Khrushchev believed that he was now in a position to pressure Kennedy into an agreement on Germany, which was Khrushchev’s primary foreign policy concern. Kennedy’s primary interest was in discussing a nuclear test ban treaty, which he felt was essential to slowing the arms race and nuclear proliferation, one of Kennedy’s most pressing concerns. The idea of a test ban treaty had been discussed for several years, but the two sides were never able to get past their disagreements on how such an agreement would be enforced.

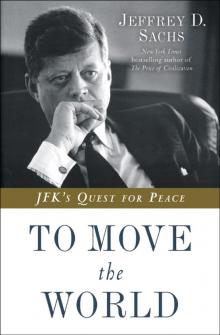

Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev with President Kennedy at the start of the Vienna Summit (June 3, 1961).

At the Vienna Summit of June 1961, Khrushchev ensured that Germany and Berlin, rather than a test ban treaty, dominated the discussion. Khrushchev told Kennedy that the Soviet Union would recognize the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) and end Western access rights to West Berlin by the end of 1961. America and its allies viewed access to West Berlin as a vital interest of the Western alliance, and so Khrushchev’s threat was an enormous provocation. If war came from this, it would come, said Khrushchev. He said that Berlin was a “running sore,” and that disarmament was “impossible as long as the Berlin problem existed.”42 Kennedy responded, “Then, Mr. Chairman, there will be a war. It will be a cold, long winter.”43

In fact, the difficult interchange brought the two leaders a little closer to a solution, though they certainly could not see it at the time. There were actually three German issues on the table, all intricately intertwined. The first was the Soviet desire for a peace treaty with Germany that would somehow protect the Soviet Union from future German aggression. The second was West Berlin, which Khrushchev considered to be “this thorn, this ulcer” within East Germany.44 Khrushchev viewed West Berlin as a staging post for Western spying and aggression against the Soviet Union, “a NATO beachhead and military base against us inside the GDR.”45 He wanted the Western troops out. The third issue involved the question of German rearmament, and especially German access to U.S. nuclear weapons. The implicit progress made in Vienna was a start in teasing apart these three issues. Kennedy would hold his ground on West Berlin, but would also recognize Khrushchev’s valid concerns about German rearmament. Kennedy made clear to Khrushchev in Vienna that he opposed “a buildup in West Germany that would constitute a threat to the Soviet Union.”46

History has judged that Kennedy “lost” the Vienna Summit because he was browbeaten by Khrushchev, particularly when the two quarreled over ideology. Indeed, Kennedy himself described the Vienna experience as brutal, telling a New York Times reporter that it was the “worst thing in my life. He savaged me.”47 Yet Kennedy in fact had held firm and clear: the West would not buckle under threats on West Berlin. More important, and despite all appearances, Kennedy and Khrushchev were now on a path to resolve the larger German issues, a path they would pursue successfully in 1963.

But the next act on Berlin would be a public relations disaster for the Soviet Union. As tensions over Berlin mounted, more and more East Berliners voted with their feet by crossing the line to West Berlin and from there to the West generally. During the first six months of 1961, over 100,000 people left East Germany, with 50,000 fleeing in June and July alone.48 The ongoing exodus of East Berliners was a huge economic loss to a floundering economy, but an even starker daily embarrassment in the frontline competition between socialism and capitalism. It was one of the main reasons why Khrushchev sought a long-term solution to Berlin.

As the flow of East Berliners accelerated, so did the geopolitical pressures. Finally, the East German government, with the support of its Soviet backers, moved to stanch the human flood. Berlin woke up on the morning of August 13 to a barbed wire divide, soon to be a concrete and heavily armed wall patrolled by around 7,000 soldiers and stretching 96 miles in Berlin and along the border between East and West Germany.49

Kennedy wisely did not challenge the Berlin Wall, except in a perfunctory manner, recognizing that any challenge or protest would prove empty. The West would certainly not go to war over Soviet actions on the Soviet side of the wall. Indeed, Kennedy immediately and correctly surmised that the wall might actually prove to be stabilizing in its perverse way, by removing the embarrassing and costly provocation of mass outmigration from East Berlin. As he suspected, the end of the flow of migrants from East Berlin rather quickly eased the Berlin crisis.

In fact, the overall Berlin situation seemed to Kennedy to be a dangerous snare that was certainly not worth the risks of global war. After the Vienna Summit, Kennedy had commented to his close aide Kenneth O’Donnell:

We’re stuck in a ridiculous situation … God knows I’m not an isolationist, but it seems particularly stupid to risk killing a million Americans over an argument about access rights on an Autobahn … or because the Germans want Germany reunified. If I’m going to threaten Russia with a nuclear war, it will have to be for much bigger and more important reasons than that. Before I back Khrushchev against the wall and put him to a final test, the freedom of all Western Europe will have to be at stake.50

Kennedy would continue, successfully, to defend West Berlin, but he would also recognize the need to move to a sounder, long-term position with the Soviet Union vis-à-vis Germany. That insight was crucial to Kennedy’s eventual success in 1963, and to the calming of the East-West confrontation thereafter. It was a basic strategic insight that Eisenhower never recognized or acted upon.

* The U-2 flights were seen even by the United States as serious provocations to the USSR, and violations of international law.

Chapter 2.

TO THE BRINK

The Cuban Missile Crisis

In the tense aftermath of the Vienna Summit, military budgets soared on both sides. A voluntary suspension of atmospheric nuclear testing that had lasted since 1958 fell apart in August 1961 when Khrushchev announced the Soviet Union would resume tests, breaking an explicit promise not to unilaterally resume tests that he had made to Kennedy two months earlier in Vienna. When Kennedy was told the news upon arising from a nap, his first reaction was “fucked again.”1 His closest advisers, McGeorge Bundy and Ted Sorensen, later said Kennedy felt more betrayed by the resumption of Soviet nuclear testing than by any other Soviet action during his presidency.2 On October 30, the Soviet Union detonated a fifty-seven-megaton hydrogen bomb nicknamed the Tsar Bomba, which remains the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated.3 After agonizing over the political ramifications, Kennedy reluctantly gave the order for the United States to resume testing as well. When Adlai Stevenson, former Democratic presidential nominee and Kennedy’s ambassador to the United Nations, complained about the resumption of U.S. testing, Kennedy told him:

What choice did we have? They had spit in our eye three times. We couldn’t possibly sit back and do nothing … The Russians made two tests after our note calling for a ban on atmospheric testing … All this makes Khrushchev look pretty tough. He has had a succession of apparent victories—space, Cuba, the Wall. He wants to give out the feeling that he has us on the run … Anyway, the decision has been made. I’m not saying that it was the right decision. Who the hell knows?4

The two superpowers had entered an icy and dangerous phase of the Cold War, exactly the opposite of what both Kennedy and Khrushchev had hoped for at the start of 1961. In January 1962, when asked about the great

est disappointment of his first year in office, Kennedy answered: “Our failure to get an agreement on the cessation of nuclear testing, because … that might have been a very important step in easing the tension and preventing a proliferation of [nuclear] weapons.”5 The arms race, the Bay of Pigs, the confrontation in Vienna, and other events had eclipsed the early hopes.

Both countries pursued an aggressive agenda. Military budgets grew. Nuclear testing resumed. The Soviet ultimatum on Berlin was repeated, and the U.S. rejection of it held firm as well. In October 1961, Kennedy had his deputy secretary of defense, Roswell Gilpatric, give a blunt speech outlining America’s nuclear superiority, significantly upping the ante. For the first time, the U.S. government publicly spelled out the vast nuclear advantage of the United States over the Soviet Union.6 This was enormously revealing to the public, especially given Kennedy campaign rhetoric about the “missile gap.”

Khrushchev was deeply undercut politically by the speech, as his domestic foes and competitors clearly recognized. Gilpatric’s revelations called into question the Soviet capacity to make good on its threats. More fundamentally, the revelation of the U.S. nuclear advantage undermined Khrushchev’s basic strategy of peaceful coexistence, by giving ammunition to Soviet hardliners who claimed that the Western alliance was out for a first nuclear strike against the Soviet Union. Khrushchev found himself increasingly cornered at home, in part through wounds self-inflicted by boasting and brashness, and in part through the arms race itself. He had overplayed his response to Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs blunder, and found Kennedy to be a tougher foe than he had expected.

The Price of Civilization

The Price of Civilization To Move the World

To Move the World